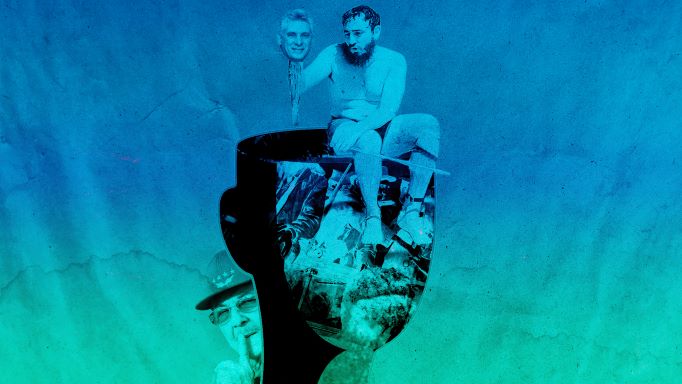

What do the commander of the Cuban Revolution Hubert Matos and the Cubans facing requests for sentences of up to 30 years of imprisonment for participating in the 11-J protests have in common? Nothing, except that both Matos, in 1959, and they, in 2021, were charged with the crime of sedition. Matos was also charged with treason.

This is where the similarities end. While in 1959 and the following years Hubert Matos being sentenced to 20 years in prison seemed crazy, and an injustice, what can one say more than 60 years later given the requests for sentences of up to 30 years in prison for Cubans who only expressed their dissatisfaction with the regime?

Each difference between the circumstances surrounding Hubert Matos and those of the Cubans who face the threat of these disproportionate sentences exposes the Cuban judicial apparatus, which is subjugated to the regime and increasingly dissociated from reason and justice.

Hubert Matos was a commander with officers and troops under his command, such that the organization and political coherence necessary for the crime of sedition to exist could have been attributed to him and his men - although this was not demonstrated in the trial. The 11-J protesters, on other hand, emerged to demonstrate their discontent and weariness with their destitution and lack of freedom, and to demand change, in a spontaneous manner, which makes the charge of sedition ridiculous.

Commander Hubert Matos and the men he commanded had weapons, while the 11-J protestors did not - not even those accused of throwing stones at the police and the ?revolutionaries? who responded to Miguel Diaz-Canel's call for violence.

In all the photos and videos one can see these revolutionaries armed with sticks, with the intention to use them, thereby obeying Díaz-Canel's orders for them to fight. The demonstrators who allegedly assaulted policemen, and some revolutionaries, did so with stones because it was what was readily available.

Was the late Fidel Castro more forgiving than his successor, Raúl Castro, and the latter's spokesman, Díaz-Canel?

Such a statement would be a mistake. If there was one thing Fidel Castro showed throughout his existence, it was a total lack of mercy towards his political adversaries, even if they had previously fought by his side and risked their lives to overthrow Fulgencio Batista, such as Comandante Hubert Matos.

In fact, in his book How the Night Came, Matos recounts that, before the trial, Fidel Castro instructed mobs to chant the mantra of the moment: "Paredón" (firing squad). The crowds complied, taking for granted that if Fidel Castro claimed ? even without a trial and without having presented evidence ? that Matos had committed treason and sedition, it was true.

This is another difference between Matos' conviction and the requests and possible sentence for the 11-J protesters: the regime no longer has mobs blindly demanding the death penalty for dissenters.

In 1959, having Comandante Hubert Matos shot would have been more costly, politically, than imprisoning him. In 2022, trying for sedition and seeking severe sentences for Cubans who demonstrated peacefully and others who engaged in public disorder and disobedience already comes at a political cost for the regime: it will no longer be able to deny that it is holding political prisoners, because sedition is a crime of a political nature.

However, the regime is more afraid of the erosion of popular support that was manifested by the protests of July 11, which were unprecedented, and the possibility that they will recur. Thus, it needs to teach Cubans a lesson, and the most effective way to do so is to punish the demonstrators, many of them minors, with harsh prison sentences that can only be applied for charges like sedition.

This is the first function of these ruthless sentences for the demonstrators. The second is that the regime will be able to use them as bargaining chips in future negotiations, like it used Alan Gross in the past.

Rather than making them serve their entire sentences, as Hubert Matos did, the regime might be interested in getting them off its hands with an offer they can’t refuse: leave or stay, but in prison, for 30 years; or perhaps some perquisite in potential negotiations with the European Union or the United States.